I have spent a great deal of my life trying to figure out how my work ‘fits in’ to the contemporary art world. To be clear, I’ve struggled with what ‘ism’ or trend or group might my work belong to so that I might explain my peculiar approach to art making.

In this quest for clarity, I have observed what seem to be two very distinct approaches that artists take toward making and marketing their work. With each comes certain criteria for achieving success, at least in terms of financial success.

The first approach, and I would venture to say, the one consisting of the largest number of participants, is the one where artists paint, draw, execute, build, etc. because they are compelled to do so. They may or may not go to some level of college for art and they may or may not get any instruction in the current or recent stylistic innovations and inventions being poured over. Regardless, they do what they do out of a stubborn belief that making art is the thing they want to do. As a result they become part of the ‘art world’, de facto members because of their chosen profession. I know many artists of this type who would say just the opposite – that they’re not now and never want to be part of the art world. Nonetheless, they are. Each one produces what someone would characterize as art and as such they are the soldiers that make up the phalanx of ‘art producers’ that populate the art world.

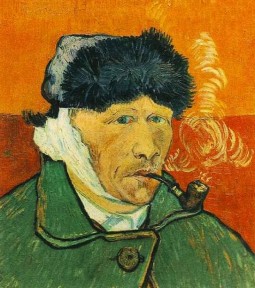

The challenge for this group comes in when they are trying to figure out how to get paid for what they do. I mean, with so many individuals expressing their feelings and thoughts in a market place that tries to normalize everything, there is no clear path from making something because you’re compelled to and finding someone interested in buying it. This is compounded, of course, by a broad base of art producers that cuts across all kinds of socio-economic levels. Yet there is a limited number of art collectors outside of the upper and upper-middle classes. Nonetheless, these artists have, want, plan, hope or otherwise try to get their work out there. The great 20th century demigod of this approach was Vincent Van Gogh. (I know, he’s from the 19th century but the romanticizing of his life didn’t happen until the 20th.) He is the poster child for the ‘starving, misunderstood’ artist.

Some (small percentage) succeed. The vast majority of this army of proletariat artists doesn’t. They produce and don’t sell or they sell something once in a while. Even in the recent boom markets for art, this remains true. They produce vastly more than will ever end up in the hands of others for any price, like mom-and-pop factories producing clothes that no one wants nor often understands.

Then, of course, you have the other group. The ones, like Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, and of course Tadashi Murakami, who went to school, taught, got the requisite MFA and PhD, studied the market and realized through analysis where the market was.

Then, he made his work to fit it. He latched onto a group in Japan, otaku culture, and used it as the jumping off point for creating his own ‘technique’ called Superflat (aka – animation like) and he combined it with the creation of a series of characters in a sort of combined pop- art meets anime approach.

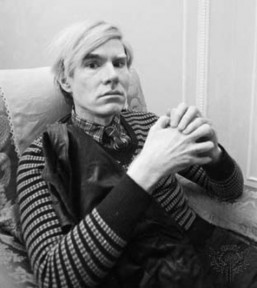

He’s not the first to follow this approach to marketing oneself in the art world. In fact, it’s been argued effectively that this was certainly Andy Warhol’s approach to making art and the market, along with many others before. The result here is that Murakami’s market analysis was successful and the thorough marketing of his ‘style’ has helped launch him to the heights of the market. As Murakami explained in a 2001 essay, quoted in Wired magazine:

“I set out to investigate the secret of market survivability—the universality of characters such as Mickey Mouse, Sonic the Hedgehog, Doraemon, Miffy, [and] Hello Kitty.”

I believe that the majority of artists who follow this approach, at whatever level they set for themselves, achieve success to a much higher degree than the previous approach. And it’s for good reason. They recognize what the other group struggles with, that in the end it’s all about commodity and as Murakami succinctly states ‘market survivability’. The art world where the money is isn’t a think tank really or a Victorian romance novel, though there are some few places where that exists. It is a retail establishment controlled by the vicissitudes of people, corporations and institutions of wealth, each of whom has some motivator or objective to satisfy. An especially good book that I was encouraged to read, “Seven Days in the Art World” by Sarah Thornton, helped me to see this very clearly. Whatever those of us growing up in the 60’s and 70’s thought the art world was, it is not that anymore.

So, we have these two groups of artists, the ‘compelled to create’ group who may both lack a certain market understanding and yet continue to produce art for its and their own sake and the artist as marketer and object producer – Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, etc.

Well, into this neatly organized marketing structure comes one of the newly coined ‘isms’ termed Relational Art or Relational Aesthetics. It was coined in 1996 by French theorist Nicolas Bourriaud. The essence of the idea is neatly captured by him here:

Relational Art…”main feature is to consider interhuman exchange aesthetic object in and of itself.” -Bourriaud.

From the website of Anthony Carriere, “According to Bourriaud, relational art encompasses “a set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space.” (Bourriaud 2002:113) A relational artist might, for example, convert a gallery space into a temporary stand for serving coffee, with the addition of background music, suitable lighting, books to read, and comfortable chairs. The artwork here consists of creating a social environment in which people come together to participate in a shared activity. Bourriaud claims “the role of artworks is no longer to form imaginary and utopian realities, but to actually be ways of living and models of action within the existing real, whatever scale chosen by the artist.” (Bourriaud 2002:13). In relational art, the audience is envisaged as a community. Rather than the artwork being an encounter between a viewer and an object, relational art produces intersubjective encounters. Through these encounters, meaning is elaborated collectively (Bourriaud 2002:17). Bourriaud believes this collective encounter can be both democratic and microtopian.”

It seems to me that rather than Bourriaud ‘discovering’ something here, rather he’s found a way to encapsulate what many artists of the first group, myself included, have been doing for a long time. The idea as I perceive it is that relational art takes into account the role of the social interaction the artist creates, enhances, produces or just generally effects. The art is something that interacts with the participant, rather than is ‘seen’ by a ‘viewer’. It seems to indicate that the artwork itself IS the interaction, not something that has been produced as a ‘thing’.

I find this concept intriguing because it’s something that’s been going on through a variety of artforms for a long time. The ‘happenings’ that were so engaging and consuming of the event space were at their best this kind of thing. In fact, this is also true to some degree of performing arts. The best performed art experiences are sublime and engaging in a way that transcends the specifics of the moment.

So, now, we have this somewhat loosely defined yet compelling argument for a form of art characterized as ‘new’ – an art of the experience. The event is the thing. Like many an art opening where more than a few of the people at the opening would have had a hard time telling anyone whose work was on the walls but they could tell you what the ‘party’ was like.

I have felt for some time that my work is like that. Though the production of my work has been objects such as photographs, drawings or paintings, these works have never been about some kind of private interaction. Instead, they are illustrations of the experience of what has happened. Yes, the works are records or documents of a process and yes, they are seen after the event or process is over, but the final product isn’t a product set outside of what took place to create it. In fact, with some exceptions regarding the stated parameters of relational art as suggesting that it be made of the space between the artist and the participant, my art and art making process are precisely what it purports to declare:

- Relational Aesthetics is a way of considering the productive existence of the viewer of art, the space of participation that art can offer.” -Bourriaud.

- In Relational Art, the artist is no longer at the center. They are no longer the soul creator, the master or even the celebrity.

- The artist instead, is the catalyst.

- They kick-start a question, frame a point of consideration, or highlight an everyday moment. And then, they wait. They wait for a response from the random stranger, the passer-by, the usual suspect – you and I.

So, with all this in mind – the two-fold approach to art making (art ‘inspired by the muses’ and art produced for the market), I wonder how this new relational approach to art gets com-modified by a system that assigns great value to objects based on a presumed or invented cultural significance? Just as is the case with objects, we have the ability to produce an endless flow of concepts and interactions that form the basis of the examination of human endeavor, aka art, but still have limited ways how to incorporate these things effectively into a system where the producers are able to survive financially off their work or the pseudo-historical institutions are able to effectively promote this work. There are examples of relational art that are included in major collections but how far it has succeeded in being incorporated into anything but a small slice of comprehensive art market remains unclear. Nonetheless, it is interesting once again to see that one of the presumed roles of art, certainly since Duchamp, has been to create art that ‘can’t be’ processed and turned into a commodity knowing all along that this is the goal – to turn exactly the most difficult production or process into something that can be sold.

A few artists whose work is considered relational are Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Jens Haaning, Angela Bulloch, Liam Gillick, Andrea Zittel, Philippe Parreno and Gillian Wearing.